As critics line up to suggest Kamala Harris is unqualified to be President of the United States one wonders if any of them have actually read her memoir.

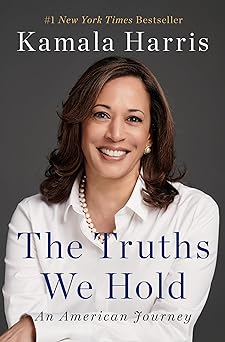

The team at Sky News seem to largely base their analysis on her somewhat raucous laugh. But The Truths We Hold: An American Journey, first published in 2019, charts Harris’s time as a state prosecutor and senator, allowing her to claim some significant policy achievements.

It is apparently compulsory for any American politician with national ambitions to write a biography, a temptation that in most cases should be resisted.

Not surprisingly, Harris’s book has leapt up the bestseller lists since she was effectively nominated as Biden’s successor, competing with JD Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy for sales.

The Truths We Hold is a more political manifesto than Vance’s book, written when Harris was already thinking of national office.

It is therefore less revealing, although it stands up well in comparison with Hillary Rodham Clinton’s, 2013 offering, Hard Choices.

While she is overly fond of cliches, and at times her book reads like a policy primer, Harris is good at humanising her issues, none more heartbreaking than when she describes the cruelty of Donald Trump’s immigration policies when he was president, which saw toddlers snatched from their parents and women abused in detention centres.

One might also read Harris’s book for insight into the appalling state of American justice, health care and persistent racism.

(At one point she mentions that within the city of Baltimore, there is a 20-year gap in life expectancy between rich white areas and predominantly black Clifton-Berea where the TV series The Wire was filmed.)

She is good at mixing personal stories with hard facts. Her discussion of the disasters of American health care is framed by the story of her mother’s death from cancer, which involved long periods of unsuccessful chemotherapy.

Towards the end of her life, her mother said she wanted to return to die in India, but she was too weak.

There is no suggestion this book is in any way ghost written, as was the case for memoirs by Donald Trump and Prince Harry.

The language feels authentic, although there are too many cliched expressions (sample: “even in the sausage-making of politics, inspiring things can happen and good work can be done”).

As if to emphasise this is her own work, there are a swag of family photographs at the end of the book.

While there has been a great deal of media attention on Harris over the past few weeks, her story is not necessarily well known.

The constant emphasis on her as a “diversity candidate” misses the complexities of her life, which has crossed class and education divides and reflects the realities of racism.

Arguably Harris is better qualified than any incoming president since George Bush Sr. Not only has she been the district attorney and senator for the country’s largest state (California), she sat beside President Biden for four years and met almost every significant foreign leader.

As a senator, she served on the Intelligence Committee, where she learnt a great deal about the possibility of cyber interference in election results.

A supportive childhood

Harris was born in 1964, the first year of Lyndon Johnson’s presidency and the era of the civil rights movement.

Her father, Donald Harris, came to the US from Jamaica and became a distinguished professor of economics at Stanford, although his Marxism seems to have been quietly discarded by his daughter.

Her parents divorced while she was quite young and her mother, Shyamala Gopalan, was the dominant figure in her childhood. Gopalan had moved to the US from India as a student, becoming an academic and a renowned breast cancer researcher.

Harris says little about her father in the book, though she includes photographs of visiting his family in Jamaica as a young girl, and appears to have stayed in touch with her paternal grandparents. Revealingly, he is not included in her wedding photographs.

Harris seems to have had a very supportive childhood in California’s Bay Area, surrounded by extended family and friends.

She first went to school in Berkeley, the second year that bussing was used to desegregate the school system.

This was a deliberate, and contentious, policy of mixing students from very different areas by bussing them to school.

After a brief time in Montreal, because of her mother’s career, Harris went to Howard University in Washington, the preeminent Black University in the US.

Here is an interesting contrast with Barack Obama, who was an undergraduate at Occidental, a prestigious liberal arts college in southern California, before transferring to Columbia university.

Harris charts her moves through law school to becoming a prosecutor, a useful career for someone running against a convicted felon.

In 1998, she moved to the office of the San Francisco district attorney, where she did policy work and started to think of running to become a DA herself.

I suspect there is more to be said about Harris’s ambition for political office than she reveals here.

Certainly she grew up very aware of the civil rights movement, and working in the DA’s office she not only became interested in policy, but met people who would become important in this and future electoral campaigns.

Expect to hear a lot in the next few months about her role as San Franciso DA (she was elected to the role in 2004) and later as California attorney general (from 2010), as her opponents paint San Franciso as Sodom and Gomorrah by the Bay, and Harris as soft on crime.

Conservatives will point to her early role in defending the right of same-sex couples to marry as another example of her crazy, leftist politics.

But not all of California is rich and woke, and in her memoir, Harris stresses the struggles of many Californians, especially those caught up in the financial collapse of 2007/8.

Her state was hit particularly hard by massive foreclosures. She went to battle with the banks in defence of people who lost everything.

Achievements

Harris can claim two significant achievements during her time in state politics. She forced the major banks to greatly increase how much they reimbursed to people caught up in the crisis. And she made significant changes to the penal system.

“I have spent almost every day working … on reforming the criminal justice system,” she writes, and as senator she worked on reforming bail and on decriminalising marijuana.

Harris is good at describing her early political campaigns, in which she presents herself as the underdog who always comes through.

But there is a lot we are not told: she met her husband, Doug Emhoff, a lawyer, in her late forties and there is a discreet silence around her romantic and sex life before Doug.

She writes movingly of how she became enmeshed in an extended family with Emhoff’s former wife and two children, but again she leaves certain questions unanswered.

For instance, Emhoff is Jewish and was enlisted by Biden in government moves to combat antisemitism.

I would have liked some reflection from Harris on how the couple have managed the contrast between their very different ethnic and religious backgrounds.

Attacks on Harris for being childless pass over her role as a stepmother, which is clearly important to her.

Family dinners were important: at some point we might expect a Kamala Harris cookbook.

No political gossip

Harris became a senator in 2017. There are a few interesting insights into the workings of the Senate, although again she is too discreet to reveal much of interest.

The book’s final substantial discussion covers the bitter Senate battle to ratify Trump’s nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the US Supreme Court in 2018, despite claims of his previous sexual misconduct.

Harris wrote this book in 2018, midway through the Trump presidency, and while she is very critical of his administration and some of its senior figures, there is little that tells us about her relations with senior Democrats.

Obama, the Clintons and Biden are only mentioned in passing. Anyone looking for political gossip will be very disappointed.

As one reads on, The Truths We Hold increasingly becomes a primer for the next campaign, and later that year Harris announced her candidature for the presidency.

In the Democratic fight for nomination she did badly, losing out on her left to senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren and on her right to Pete Buttigieg and Joe Biden.

An admission: I was more impressed by her in the 2020 campaign than most Democrats, and she was an obvious choice for Biden as vice-president.

The right claim she was only picked because he wanted racial and sexual diversity, but this ignores the substantial record she already had as a DA and senator.

Harris had become close to Biden’s now dead son, Beau, when he was attorney-general of Delaware, which was certainly a factor in Biden’s choice.

Kamala Haris (right) with Joe Biden. Internet Photo.

There is an echo here of Trump’s choice of JD Vance, who had become a close friend of Don Jr.

The Truths We Hold ends in sermon-like fashion, exhorting us to remember that “we are still one American family and we should act like it”.

Can she win?

So can Harris win? Will Americans vote for a woman of colour and one who comes from the most liberal part of the country?

Given Trump has the unwavering support of perhaps 40% of those likely to vote, Harris’s chances depend essentially on her ability to persuade millions of people, above all young women and people of colour, to turn out on November 5th. I’d put a small wager on her succeeding.