On March 12, Kenyan author Mukoma wa Ngugi announced on X (formerly Twitter) and on Facebook that his father, the renowned Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, had “physically abused” his late mother, Nyambura.

This revelation has attracted significant attention. At the time of writing this piece, the Twitter post had amassed millions of views, thousands of reposts, and close to a thousand comments.

A tweet by South African author Zakes Mda, in which he praises Mukoma’s statement as “the bravest thing any son of an icon can do,” has also gained substantial traction.

In the days following the initial post, Mukoma has said that relatives and friends have accused him of lying.

Meanwhile, the news has been covered by Nigeria’s Premium Times and several Kenyan media outlets, including a think-piece by Kenyan writer Tony Mochama that mocks Mukoma for considering social media a “safe space” to expose his father’s “toxic masculinity.” Ngugi has yet to issue an official response.

However, in a tweet published on March 20, Mukoma’s sister, Wanjiku Wa Ngugi, posted a photo of three siblings with Ngugi, captioned: “Just chillin’.”

In the absence of an official statement, this tweet appears to be a display of solidarity and perhaps a rebuttal to Mukoma’s accusations.

The silence from the African literary community regarding this allegation is worth noting, with much of the public responses coming from the non-literary side of the Kenyan public.

While comments from figures like Njambi McGrath, Maneo Mohale, Siphiwo Mahala, Donald Molosi, Niq Mhlongo, Stella Nyanzi, and Iquo D’Abasi can be found under the original Twitter and Facebook posts, in addition to Zakes Mda expressing his support, the overall public response by African writers and academics has been more muted than one might expect for such a revelation. This could stem from several factors.

Firstly, there may be a sense of controversy fatigue; social media has become saturated with disputes, leaving people weary of engaging in yet another conflict or worried about being dragged for dragging someone.

Additionally, the deeply personal nature of the allegation – a son confronting his father – can make observers feel as though they’ve inadvertently intruded into a private family matter, witnessing something unsettling that one is not supposed to have seen.

The reason we are addressing the allegation at Brittle Paper is not to adjudicate Mukoma’s claims against Ngugi or to dissect public opinion. Our mandate is to document the African literary landscape, including stories that are fraught with discomfort and complexity.

Mukoma’s claims about his father is significant not for its potential to sensationalize but for what it reveals about the forces that shape the African literary community.

In pursuing this story, I have had to confront the ethical tightrope between public interest and the risk of exacerbating personal anguish, particularly given that these are still only allegations and that Ngugi has yet to respond.

Much of this piece is heavily weighted on what Mukoma shared with me via WhatsApp and a phone call, in part, because neither Ngugi nor the close family members I reached out to responded.

But I had off-the-record conversations with other people in the community, and while I can’t include anything they shared, it gave me perspective.

This report, therefore, is presented with an acknowledgment of its limitations and the readiness to adapt as new information emerges.

Let me begin by noting that the claim that Ngugi beat his wife stands in stark contrast to his image as an activist who built a decades-long, global following by speaking to power on behalf of the oppressed. Ngũgĩ’s stature as a luminary in African literature is undeniable.

His writings fearlessly denounce colonialism, dictatorship, and corruption. His advocacy for African languages and literature is unmatched and has earned him global acclaim and many accolades.

Little surprise that Mukoma’s statement has sparked a heated debate and proved to be divisive. On the one hand, someone like Mona Eltahawy, who has written a lot about intimate partner violence, treats Mukoma’s statement with the same gravity of a #metoo story.

In a message to us, she remarks: “I salute Mukoma for his statement. So often, women plead for the men in their lives to believe them and speak out. That this is a son exposing his father’s abusive behavior is incredibly important.”

On the other hand, his allegation against his father has been met with skepticism and outright denial by some, as is evident in the collection of responses to his initial tweet.

Others have criticized him for bringing private family matter to the public and worried over the potential impact of such an allegation on his father’s legacy.

Many see his statement as an act of impropriety, essentially a case of airing dirty laundry. He has also been accused of everything from pandering to Western feminism to charges of immaturity, being un-African, and exploiting his father’s plight for personal gain.

The unfolding drama reveals complex layers, particularly around the issue of privacy, which turns out not to be a straightforward one. Last year, Kenyan journalist Carey Baraka published an intimate profile of Ngũgĩ, depicting his frail health and solitary life, leading Mukoma to defend his father.

Despite Ngũgĩ’s public approval of Baraka’s piece, Mukoma criticized it for unethical oversharing.

He questioned the necessity of certain details in storytelling, labeling anything superfluous as “gossipy excess.” Now, as Mukoma shares intimate details of his parents’ marriage, the tables have turned, with many accusing him of the same oversharing. People are also asking why now?

In our conversations, Mukoma shared with me that his decision to come forward was not impulsive but part of a longer journey to address what he perceived as an injustice to his mother’s memory.

“It is not a question of ‘why now.’ I’ve had a pinned tweet since 2022. This has been a longstanding conversation for me, not just an abrupt revelation.”

In the tweet to which he refers, him writes: “It hurts to see my late mother, Nyambura (my daughter is named after her) being systemically erased from the @NgugiWaThiongo_ story. We literally (of course) and figuratively would not be here if it was not for her keeping us glued together through the political persecutions.”

These allegations against his father seem to be part of a longer journey towards finding his mother, who lived a very difficult life, whose experience as a parent and a wife in a time of anti-colonial struggle took its toll in ways that, for Mukoma, has not been properly addressed.

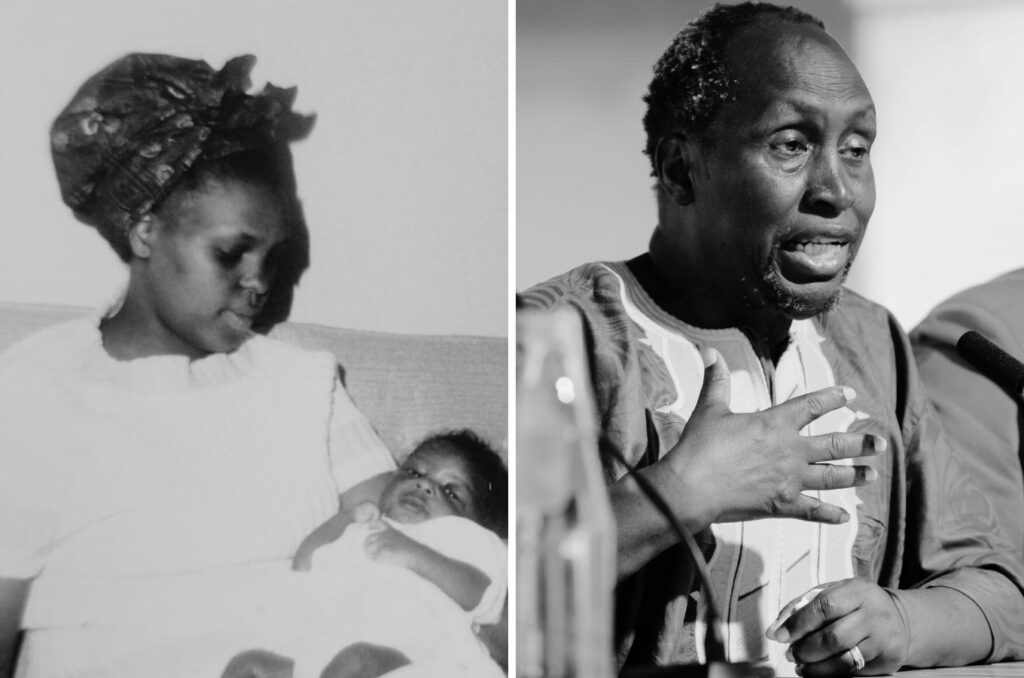

The relationship between Ngugi and Nyambura goes back to the early years of his literary career. In his 2016 memoir, Birth of a Dream Weaver, Ngugi recalls their relationship.

They had known each other since childhood, growing up in the same neighborhood and attending the same schools. While her formal education ended prematurely, he advanced to Makarere University, perhaps exemplifying how men benefited from colonial patriarchy while women were systematically excluded from similar opportunities.

“But,” writes Ngugi, “the more our paths parted, the more rapidly our hearts drifted toward each other, and by the time I went to Makerere in 1959, we had entered into a soul pact we always knew was coming.”

He was at Makarere University while she was pregnant, and he writes about missing her a lot. When he began drafting his first novel Weep Not Child, she inspired one of the main characters.

He notes that “the thought of her smile at finding her name inhabited by a character in a book… adds to the call of the muse.” This romance didn’t last forever.

They eventually parted ways, after years of navigating some of the most traumatizing experiences of political victimization, which placed considerable strain on the family. Nyambura died in 1996 and is buried in their ancestral home in Limuru.

The memoir covers the early period of Ngugi’s life and so, it makes sense that, it does not get into the troubles of their relationship. But if we went by the memoir, Ngugi and Mukoma remember Nyambura differently.

Nyambura who is a muse, a soulmate in Ngugi’s memory becomes in Mukoma’s story a neglected, abused spouse. In a whatsapp message, Mukoma recalls the painful memory in which “a neighbor at some point asked why we buried her like a dog because her grave was so overgrown. In Gikuyu speak you cannot be asked a worse question.

Her gravesite is much better now, but that is a question no family should have to be asked.” For Mukoma, this is a deeply personal issue, rooted in his family’s experiences during the Moi regime in Kenya.

Mukoma shares a memory of his mother being protective of his father: “we lived through the horrors of the dictatorship with an exiled father and an embattled mother with six kids doing as best as she could.

Anyone who has been on the receiving end of a dictatorship will know I am not telling the full story here.

There were days when we did not have to eat or enough school fees (yes, I was sent home on many occasions because of this).

But in the midst of all that she called a family meeting and said, on the pain of her death, she will never want us to disown our father just to get relief from the dictatorship – as some of the other families had done.”

In this complex interplay of devotion, politics, and survival in a time of postcolonial violence, Mukoma wants to center his mother’s courage as opposed to her victimhood.

“She was at different points a teacher, farmer, small business owner. She did all that she could to keep us in school, fed us…She was very protective of my father and us her children.”

What comes through in this controversy is a reminder of all that we leave out when we tout the 20th century as this period of epic political triumph carried out by swashbuckling African writers, mostly men.

What is lost in this triumphal history are the traumatized children and neglected wives, homes ravaged by the twin power of patriarchy and colonial violence.

Mukoma’s accusations against his father of mistreating of his mother, while deeply personal, highlight a broader historiographical issue.

It serves as a reminder that we’re not telling the full story when we overlook the ways in which African literature, like most other literature, was forged in the heart of patriarchal power.

Mda’s message of support to Mukoma suggests that this is a deeply structural issue, referencing his own father’s mistreatment of his mother and Nelson Mandela’s alleged mistreatment of his spouse.

The mythologies we weave of our heroes are deeply flawed in the ways that it erases the intersectional complicity in other kinds of oppression.

Again, Mukoma’s claims about Ngugi’s treatment of Nyambura asks us to consider what other stories linger in the shadows of the grand narratives we construct about the origins of our cherished cultural moments.

Mukoma’s claims are not just personal but deeply political and archival, calling attention to the invisible labor, sacrifices, suffering, misuse of power, and other factors that shape the spaces we hold dear and sacred.

We have always told the story about African literature with people like Ngugi as the protagonists. The scandal at the heart of Mukoma’s allegations is that those kinds of epic stories are highly edited.

There is a whole other story about who was left behind to bear children and take care of the home while our beloved male authors launched careers of a lifetime.

Those people who say that Nyambura’s story and her treatment is private matter whereas Ngugi’s activism and literary success is the public story are complicit in a culture of erasure that runs deep.

It is not just Ngugi. Think of all the men whose stories have become synonymous with African literature.

Now think of all the women, mothers, all the sisters, all the children who sacrificed to allow these men to take advantage of colonial institutions that were designed to benefit men.

For every male author that is christened “father of African literature” there is a community of actual mothers who gave up so much to get them to the spotlight. We never hear their stories.

The question I hear in Mukoma’s post is what would the story of African literature look like if Nyambura and her avatars were the protagonist?

What does it mean for the culture that someone who built a life on fighting for the oppressed may have abused others?

Sisonke Msimang has cautioned against the pitfalls of centering culture around figures who become so larger than life that we project our ideals on them.

We make them into symbols of our worlds, ask them to stand in for us and give them so much power than they, in their human frailty, can handle.

Our heroes are always going to fall short. As Carey Baraka notes, in an email message, “we like to think of our heroes as infallible, even though they are all capable of doing terrible things to the people around them…

Ngugi has been an important writer, but also, per Mukoma’s accusation, seems to have been terrible to his wife…

There are many versions of Ngugi, some wonderful, others terrible, and now we must reckon with all these sides of him.”

This echoes Msimang’s point that it is important to understand that “all [our] faves are problematic.”

They all are. It is Ngugi today. It will be someone else tomorrow. Acknowledging this does not mean that we do not make them accountable for their actions.

It simply means that we need to interrogate the culture of stanning that make us deify a handful of people as the arbiters of our cultural life.

Brittle Paper

1 Comment

Hello There. I found your blog using msn. This is a really well written article. I’ll be sure to bookmark it and come back to read more of your useful information. Thanks for the post. I will definitely return.